How Addis Ababa Can Restore Its Water Supply

Water is a lifeline for cities. Yet, in Addis Ababa, that lifeline is growing tenuous. Over the past decade, the city’s water supply has dwindled dramatically due to intense urbanization, lagging infrastructure and non-revenue losses, landscape degradation and the growing impacts of climate change. What used to be an easily accessible resource is not just disappearing but also growing more expensive — a challenge for both local leaders contemplating long-term risks and residents grappling with daily barriers to access water.

Reservoirs in Gefersa and Legedadi provide up to 41% of the city’s piped supply. These surface-level reservoirs are complemented by groundwater extracted from wells in Akaki, Legedadi and hundreds of smaller wells scattered across Addis Ababa. Combined, these sources provide nearly 800 million liters of water every day. Yet, it’s nowhere near the amount the city needs.

Preliminary assessments from a new study with the Nature for Water facility indicate a little over half of the city’s water demand is currently met. The intense urbanization of the previous few decades has had knock-on effects on the city’s water system, and with Addis Ababa growing at an annual rate of 3.8%, this trend is only expected to continue.

Informal water suppliers help meet the gap in daily needs across Addis Ababa. Photo: Eden Takele/WRI Africa

1) Address Systemic Inefficiencies

Water systems are generally considered effective if more than 75% of total supply reaches users. In Addis Ababa, that number hovers around 50%.

Every year, about half of Addis Ababa’s water supply is lost to poor infrastructure. Some of these losses come from non-metered access points and without sufficient monitoring equipment, the city is unable to recover these losses. Even more water is lost to leaking pipes across the city, where aging infrastructure and inadequate maintenance are to blame.

When water is lost in this way, it’s called non-revenue water. Non-revenue water is a huge challenge for cities around the world, especially in cities in developing countries like Addis Ababa — but global best practices exist.

Efforts to tackle non-revenue water are most effective when they combine a variety of approaches. On the technical front, utilities must prioritize pressure management: optimizing water pressure within distribution systems to reduce stress on aging pipes and minimize bursts. These interventions should be supplemented by systematic leakage control, using modern detection technologies to find and fix hidden losses.

Physical improvements should be reinforced by managerial strategies that strengthen institutional capacity. This looks like establishing performance monitoring systems to track water loss indicators, investing in staff training to build technical and operational skills, and adopting data-driven decision-making to target interventions more efficiently — Addis Ababa is making progress on this front, implementing Performance Management Contracts.

Behavioral strategies are an added piece of the puzzle: engaging consumers through awareness campaigns, encouraging them to report leaks promptly and building a shared sense of responsibility for water stewardship helps to reduce water loss.

Together, these technical, managerial and behavioral approaches form a holistic framework for reducing losses and ensuring systemic integrity.

2) Engage Large-Scale Consumers in Rigorous Water Stewardship

While Addis Ababa’s municipal water system is plagued by inefficiencies, of greater concern are the large-scale consumers that operate outside of it. Municipal service providers, like Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority, cannot regularly supply the daily needs of large-scale consumers such as the bottling and textile industries, real estate developers and high-end hotels.

With an increasingly precarious supply from municipal service providers, more private sector operators are digging their own wells into the city’s aquifers. This presents a dangerous situation: groundwater is a shared resource; thus, transparency and accountability are critical.

Despite persistent misconceptions, water is not an inexhaustible resource. When withdrawals consistently exceed natural recharge, ecosystems decline and water security collapses. In cities where the scale and impact of large water users remain poorly understood, systematically tracking withdrawals, losses, recoveries and the actual outcomes of “replenishment” interventions is critical to conserving limited resources. Replenishment, in particular, plays a vital role in restoring balance to local water systems.

Corporate leaders like Heineken have begun offsetting their water use through landscape conservation and watershed protection efforts. While these initiatives are valuable, replenishment volumes must be scientifically verified to ensure their effectiveness. Large-scale consumers have a social responsibility to conduct rigorous water accounting and use water as efficiently as possible.

Multinational corporations are already familiar with standardized frameworks such as Water Accounting+ or the Alliance for Water Stewardship (AWS) Standard, which help assess and manage water use responsibly. These frameworks should be more widely adopted by other large-scale users, such as industrial parks, as they establish clear baselines, leverage hydrological data to track changes and promote transparent disclosure of results.

3) Safeguard the City’s Watershed

Addis Ababa’s water security is greatly threatened by its burgeoning population. Under a business-as-usual scenario, where extraction rates continue without concerted efforts to protect the water, the city is on track to face increasingly worsening shortages.

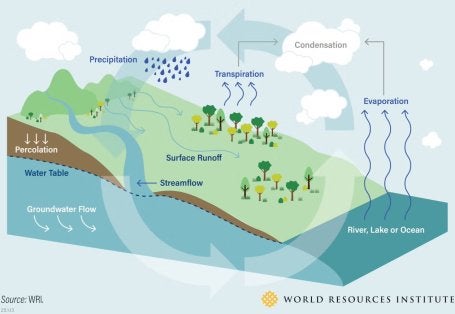

For Addis Ababa, protecting its water means investing in the protection of its surrounding watershed. Watersheds are natural areas of land that drain into a common body of water. These areas supply the water we use. The city’s watershed must be protected, especially its critical recharge zones.

Recharge zones are places like wetlands or forests where surface water can infiltrate deep into the earth’s surface, replenishing the groundwater aquifers we draw most of our water from. When recharge zones are maintained with their natural vegetation and retain their ecosystem function, rain can percolate into the aquifers below. But development and intensive farming in these areas disrupt the hydrological cycle, causing groundwater levels to decline.

Watershed protections, like the type Addis Ababa needs, require financing. New York City, a global commercial hub with tremendous water demand, began investing in the protection of its water source in the Catskill Mountains in the early 1990s and now boasts some of the world’s best tap water. Closer to home, cities like Nairobi, Cape Town, Dakar and Freetown have instituted “water funds” to channel finance from downstream users to upstream custodians who restore and protect their watersheds.

For Addis Ababa, safeguarding its recharge zones requires not just finance, but data and policy as well. For example, wetland neighborhoods, like Lebu, that once soaked up rainwater, are now paved over. Without data to identify these zones and strong land-use policies to protect them, we risk losing even more of these critical natural assets. Protecting these areas through enforceable laws is a start, but other solutions — including building artificial wetlands to manage stormwater and filter pollutants and creating public green spaces — are also available.

4) Improve Water Storage Capacity

In addition to protecting water, storing it has also proven challenging. The Dire Dam, for example, built to serve as additional reserve for water processed at Legedadi, lost much of its capacity in recent years.

The land around Legedadi and Dire dams was once a sea of green. Now, most of the trees are gone and farming reaches right up to the reservoirs’ shores, causing sediment runoff during rain events to surge and dramatically reduce the dams’ capacities.

To protect this critical infrastructure, Addis Ababa must urgently invest in protecting the landscape around its reservoirs. This means reforesting hillsides, clearly demarcating and protecting buffer zones around reservoirs, and supporting communities to shift their livelihoods away from farming to more sustainable practices like agroforestry or payments for ecosystem services.

5) Strengthen Shared Governance

Addis Ababa’s surface water supply comes entirely from reservoirs located in Shaggar City and many of its groundwater recharge zones are located even further upstream across the Oromia Regional State.

Gefersa reservoir is located 19 kilometers west of Addis Ababa in Burayu, Shaggar City, situated within Oromia Regional State. Photo: Eden Takele/WRI Africa

Stronger collaboration between the Addis Ababa City Administration, Shaggar City, and federal and regional agencies could be a game-changer for long-term water security if backed by the right policies and legal frameworks. Throughout 2025, WRI Africa hosted multi-level dialogues between these stakeholders to identify and unlock enabling conditions for proactive and water-sensitive planning. These dialogues aimed to advance the shared understanding that water doesn’t respect administrative boundaries, and urban and regional planning must reflect this reality.

Clear water governance policies can help define who does what, how costs and benefits are shared, and how administrations can work together across borders. River basin offices, as the principal authorities overseeing water management, are well placed to assume strong coordinating roles across sectors and administrative boundaries — enabling a shift towards a more connected, systems-based approach. This not only benefits Addis Ababa but also creates real opportunities for improving livelihoods in fast-growing areas like Shaggar City.

—

As we contemplate Addis Ababa’s future in an increasingly water-stressed world, we need a shared understanding that water is not an inexhaustible resource, and our access to it in the coming decades depends on our collective action now. Cities must protect their water like their future depends on it, because it does.

Keeping the taps flowing requires strategic and systems-based approaches that recognize the role that every stakeholder has to play. The time to act is not when the wells run dry, but now, while we still have a choice.