Turning the Tap on Food Loss and Waste in Kenya

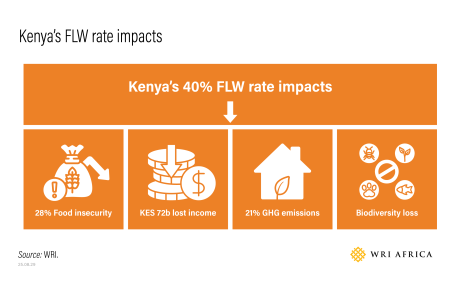

Africa is the only region where hunger is rising. Today, more than 300 million people—one in four Africans—are hungry. If current trends persist, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2025 report projects that Africa will account for over 60% of the world’s hungry by 2030. In Kenya, a quarter of the population faces severe food insecurity, even as up to 40% of the food produced is lost or wasted each year—an estimated KES 72 billion (US$578 million). This not only squanders scarce resources such as land, water, labor, and energy but also drives climate change, contributing 21% of Kenya’s greenhouse gas emissions.

While often discussed together, food loss and food waste are distinct: food loss occurs earlier in the supply chain—on farms or during handling, storage, and transport—whereas food waste occurs later, at retail, in restaurants, and in households.

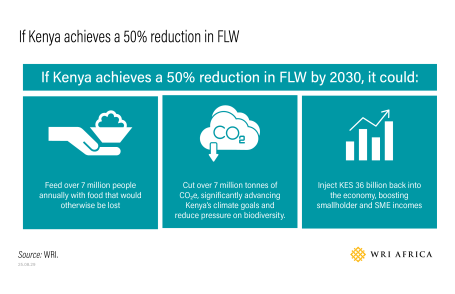

Kenya has committed to tackling food loss and food waste through the 2014 Malabo Declaration (now succeeded by the Kampala 2025 Declaration) and SDG 12.3, which aim to halve food loss and food waste by 2030 and 2035, respectively. Research led by WRI and the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) highlights the potential of reducing food loss and food waste to enhance food security, improve livelihoods, and support climate action.

Despite these commitments, progress remains slow due to limited data, weak coordination, and insufficient financing for scalable solutions.

A new WRI report, Food Loss and Waste in Maize, Potato, Fresh Fruits, and Fish Value Chains in Kenya, provides a comprehensive analysis of the scale, drivers, and policy gaps in key value chains, drawing on literature reviews, interviews, and market observations.

How much and where do losses occur in Kenya?

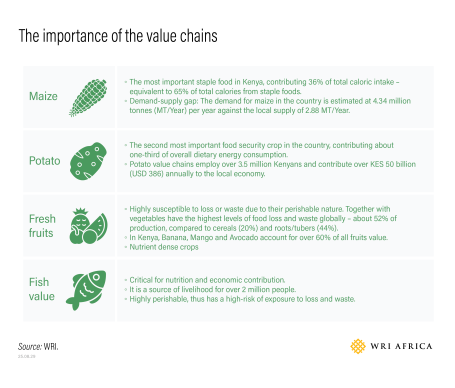

Food loss and food waste occur across all value chains, but this analysis focuses on maize, potato, fresh fruits (mango, banana, avocado), and fish. These were selected for their importance as staple foods (maize, potato, banana), nutrient-rich sources (fruits and fish), and commercially significant commodities (mango and avocado).

Magnitude, hotspots, and drivers

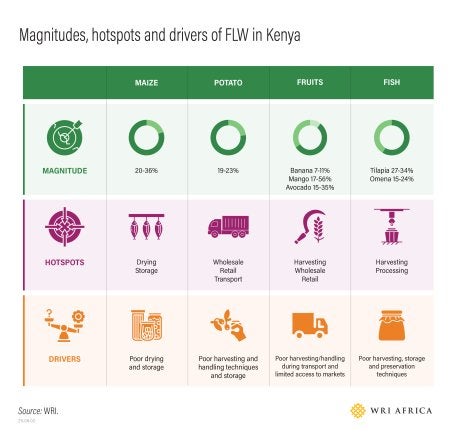

Reported food loss and food waste vary widely: 20–36% for maize, 19–22% for potato, 17–56% for mango, 15–35% for avocado, 7–11% for banana, and 15–34% for fish. Differences reflect long, complex supply chains and the fact that most studies do not track food waste or where removed food ends up. Critical loss points differ by commodity: harvesting, retail, and wholesale for potato, fruit, and fish; drying and storage for maize; and processing for fish. Leading causes include inefficient harvesting, rough handling during transport and packaging, limited storage, and outdated processing methods for fish.

Gaps in Existing FLW evidence

Four key gaps limit understanding and action:

• Limited and variable evidence: Few studies report on food loss and food waste in Kenya—just one for banana, two for avocado, three for potato, five for mango, seven for maize, and three for fish. Variations arise from differing definitions of food loss and food waste and the failure of most studies to account for waste beyond retail or track food removed from the value chain.

• Inconsistent reporting across supply chains: Many studies omit stages—maize studies often focus only on storage; potato studies sometimes skip harvesting; fruit studies rarely consider seasonal, variety, or regional differences.

• Limited data on quality losses: Nutritional losses, such as aflatoxin contamination or nutrient degradation in maize, and in fish and fruits, are rarely measured. No reviewed fish studies assessed nutritional loss.

• Insufficient attention to underlying drivers: Limited understanding of causes hinders design of effective interventions.

Innovations to Reduce Food Loss and Food Waste

Technologies and innovations can significantly cut food loss and food waste, including improved harvesting tools, appropriate fishing gear, drying technologies, insecticides, fruit fly traps, better storage (hermetic bags, silos, light-diffused rooms), cold chains, and decentralized processing for perishables. Process innovations—aggregation, contract farming, and traceability systems—improve efficiency and link farmers to reliable markets.

Adoption depends on proper training. Traditional methods are deeply ingrained, and farmers may hesitate to change. Some solutions, like hermetic bags, reduce losses but are less affordable than polypropylene alternatives. Cold chains often do not fit smallholder contexts. Process innovations, such as contract farming and warehouse receipt systems, face low acceptance due to mistrust, past negative experiences, and weak enforcement. Smallholder processing initiatives also struggle with high marketing costs and limited reach, making commercial sustainability difficult.

Kenya’s Food Loss and Food Waste Policy: Data Gaps = Action Gaps

Kenya has endorsed SDG 12.3 and the Malabo Declaration (now succeeded by the Kampala 2025 Declaration), and multiple strategies (Vision 2030/MTP III, Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy (ASTGS 2019–2029), Agricultural Policy 2021, Climate-Smart Agriculture Strategy), which recognize the need for food loss and waste reduction. The 2024 Kenya Post-Harvest Management on FLW Reduction Strategy (2024–2028) is a step forward.

However, there are still gaps that limit the potential of policy and incentives in reducing food loss and food waste in Kenya:

• Coordination systems are slow to implement

• Food loss and food waste is not recognized as a key tool for food security and climate goals

• There is no reliable system to measure or report food loss and food waste

• Food recovery and redistribution are under-supported by policy

• Farmers lack targeted incentives (tax breaks, grants, technical support) for adopting food loss and food waste-reducing technologies.

Moving From Commitment to Action

With only four years left to achieve SDG 12.3 targets, the world is off track. Kenya lacks robust monitoring of food loss and food waste, which limits its understanding of the scale, causes, and effective interventions.

Champions 12.3 is a coalition of public and private sector actors that aims to achieve this SDG goal by mobilizing governments and agribusinesses to address food loss and waste using the “Target-Measure-Act". approach: setting targets, measuring food loss and food waste, and driving change through concrete interventions

Three Strategies to Reduce Food Loss and Food Waste in Kenya

1. Strengthen measurement of food loss and food waste: Kenya lacks disaggregated data on where and why losses occur. Accurate data enables national targets, interventions, and progress tracking. Standardized tracking across value chains, stakeholder training, and integration into national reporting are critical. WRI and FAO are developing practical tools tailored to local realities, which could be game changers.

2. Scale investment in proven solutions: Technologies and practices exist, but awareness and financing are limited. Capacity building in pre-harvest checks, harvesting, drying, storage, hygiene, transport, and aggregation is crucial. Successful models—like maize cob-and-grain hubs—and lessons from export value chains (contract farming, cold storage) should be scaled domestically. Public campaigns, school programs, and retailer partnerships can shift consumer habits, encouraging portion control, proper storage, and food redistribution.

The World Bank estimates $30–50 billion is needed globally to halve food loss and food waste by 2030, yet only $1.1 billion had been invested by 2019/2020. Closing this gap requires bold public–private partnerships and sustained financing, alongside testing solutions for real-world fit, affordability, and trade-offs.

3. Strengthen policy and coordination: Kenya needs holistic strategies that move beyond sectoral approaches, placing food loss and food waste at the center. Policies must be evidence-based, grounded in accurate measurement, local drivers, and cost–benefit analysis, including trade-offs. Supportive policies for food donation and redistribution are essential. Kenya can boost impact by fully implementing its National Strategy on Postharvest Loss and Waste by establishing a well-mandated national food loss and food waste committee with county links and dedicated funding, and embedding food loss and food waste into climate commitments and sector plans to drive food security and climate action.

Download the report: Food Loss and Waste in Maize, Potato, Fresh Fruits, and Fish Value Chains in Kenya