From Planning to Progress: What Our Latest Research Reveals About Delivering Climate Action in Africa

Climate change in Africa is often framed as a challenge of missing technology, insufficient resources, or weak ambition. But recent research from WRI Africa tells a different — and more hopeful — story.

Across the continent, solutions already exist — farmers are restoring degraded land; renewable energy technologies are available; cities are experimenting with cleaner transport; governments have climate strategies. Yet progress remains uneven, and too many communities still face unreliable power, rising food prices, flooding cities and fragile livelihoods.

What is holding Africa back?

The start of a new year offers an opportunity not only to set ambitions but to reflect on what we are learning about what is, and what is not working. Drawing on the past two years of applied research and knowledge products produced by WRI Africa and our partners,across food systems, energy, cities, land restoration and forest protection, we have conducted a stock take on what we are learning about delivering climate action.

This research, developed in close collaboration with governments, communities, financiers, and implementing partners across Africa, is grounded in shared learning and real-world experience. It highlights how local governments, cities, the private sector, community groups and faith-based organizations shape everyday outcomes — from healthy ecosystems that support food production and water supply, to energy, transport and air quality — even as they remain under-resourced and too often overlooked in climate and development strategies.

One insight stands out: the biggest challenge is not finding solutions — it is delivering them where people live and work. Climate action succeeds when plans, budgets, and institutions align at the local level. When they do not, even the best ideas fail to scale.

In the village of Ilanga, DRC, a man showcases a map created by his community in order to better delimit the boundaries of particular land concessions on their traditional lands. Photo: Molly Bergen/WRI

Most importantly, the evidence is clear on one point: people care about climate action when it improves daily life — when it means more reliable food supplies, better jobs and incomes, lower energy costs, safer cities, and healthier environments, including the conservation and restoration of forests and other natural landscapes that support livelihoods and resilience.

Here, we share three lessons from WRI Africa’s latest body of research over the past two years on how climate and development can work better together — not in theory, but in practice, for people, nature and climate across the continent.

Africa’s climate and development challenge is not a lack of solutions — it’s a delivery problem

Across Africa, the frustration is familiar. Policies are in place, pilot projects work and technologies are proven. Yet farmers still lose food after harvest, health clinics struggle with unreliable electricity, and cities flood year after year.

WRI Africa’s research shows that this gap is not about ambition or innovation. It is about delivery.

In energy, for example, many health facilities are officially counted as “electrified,” reflecting important progress in expanding electricity access across the continent. But assessments show that connection alone is often not enough. In many facilities, power is unreliable, too weak, or too costly to consistently run cold chains, diagnostic equipment, or emergency services. Electrification is a critical first step — but reliability and power quality are essential to turning access into functioning health services.

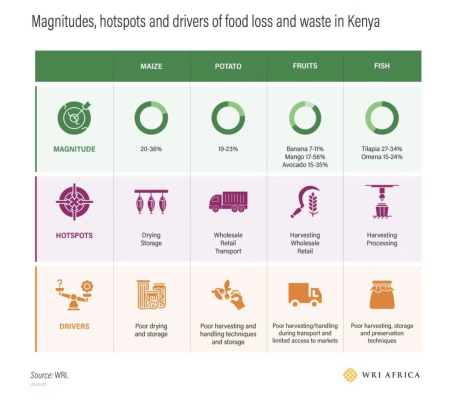

The same pattern appears in food systems. Our research across agrifood value chains shows that post-harvest losses are driven less by what happens on farms and more by what happens after crops are harvested. Poor feeder roads, limited cold storage, and unreliable electricity mean that food spoils before it reaches markets. Sustainable food production and land restoration approaches exist, but without supporting policies, infrastructure and scaling, benefits fail to reach people’s plates or restore degraded landscapes.

Climate finance tells a similar story. WRI Africa’s diagnostics consistently identify viable projects that could reduce emissions, build resilience and create jobs. Yet many never reach investment. They are too small, too fragmented, or too complex for existing financing models. The problem is not a shortage of ideas or demand — it is the absence of delivery systems that connect local projects to capital.

Taken together, this evidence points to a clear conclusion: Africa’s climate and development challenge is not about discovering new solutions. It is about fixing the systems that turn plans into functioning services — aligning policy, infrastructure and finance at the local level, where outcomes are delivered.

Subnational governments and local institutions deliver outcomes — but they are systematically under-resourced

When people experience climate change and development failures, they do not experience them as national policy problems. They experience them firsthand — at health clinics without power, on roads that wash away, in markets where food is scarce or expensive and in cities with poor air quality.

WRI Africa’s research shows that climate and development outcomes are delivered locally. Subnational governments make daily decisions about land use, water services, local roads, markets, health facilities and energy connections. Community organizations, cooperatives, domestic banks, and faith-based institutions shape livelihoods, manage assets, and influence trust.

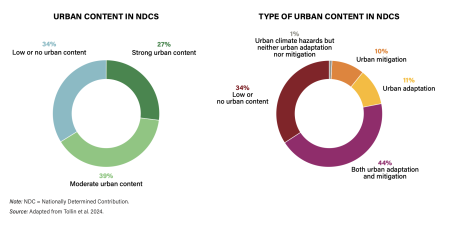

Cities are central to delivering national climate commitments, yet this is not always reflected in how climate goals are designed or financed. While many of these goals depend on urban action — particularly in transport, energy, buildings, and waste — cities often lack a formal role, predictable funding, or access to climate finance. Informal settlements are where the gap between climate planning and lived reality is often most visible — and where integrated delivery matters most. Bridging this gap is essential if climate goals are to move from paper commitments to tangible results.

Urban content in Nationally Determined Contributions as of July 2023 (n = 194)

Yet across countries, a consistent mismatch remains. Responsibilities have been devolved, but resources have not. Local governments are expected to deliver climate-resilient services without predictable fiscal transfers, borrowing authority, or access to affordable finance. Cities can identify urgent infrastructure needs but lack the revenue tools to fund them. Local financial institutions already invest in productive sectors but are rarely integrated into climate finance strategies.

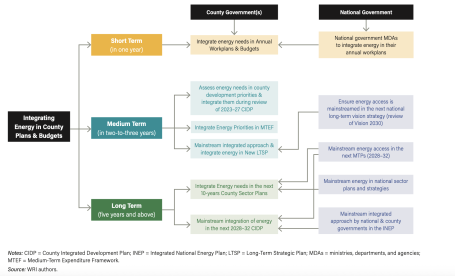

WRI Africa’s research also shows what becomes possible when subnational institutions are given the right tools. In Kenya, a county using integrated energy planning now includes clear investment priorities in their budgets and funding proposals, making it easier to engage donors and private partners.

Opportunities and steps needed to integrate energy in Makueni’s County Energy Plan

Working at the subnational level also reveals why local planning matters. Even counties with similar electrification rates can have very different demand profiles and investment needs. In some places, household demand dominates; in others, agro-processing, markets, and public facilities drive electricity use. These differences shape what least-cost, high-impact solutions look like — and they are invisible in national averages.

WRI Africa’s research challenges the idea that the continent’s solutions must come primarily from external sources. It shows that local institutions already understand their priorities and constraints — but need data, planning and learning tools, and finance aligned to their realities. Unlocking progress depends less on creating new institutions, and more on empowering the ones already on the ground.

Integrated planning beats siloed action — and livelihoods are the entry point for public support

For most people, climate change is not an abstract global issue. It shows up in practical ways: whether food reaches markets, whether transport is affordable, whether electricity supports businesses, and whether cities are safe during floods or heatwaves.

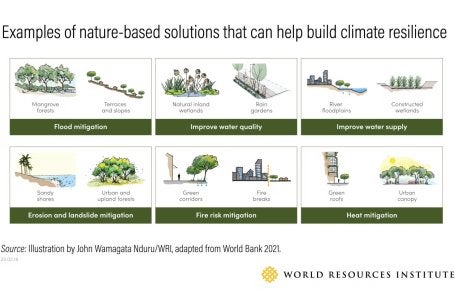

Urban resilience brings these connections into focus. In fast-growing African cities, decisions about transport, housing, drainage, energy, and land use shape exposure to floods and heat. WRI Africa’s research shows that nature-based solutions such as urban forests and green-gray infrastructure can reduce these risks. However, scaling them depends on integrating them into planning and budgets, strengthening early project preparation and clearly demonstrating their resilience, climate and biodiversity benefits to unlock infrastructure, domestic, and climate finance — while remaining responsive to community needs.

WRI Africa’s research consistently shows that these challenges cannot be solved one sector at a time. Food security depends on energy, roads, and markets. Energy access delivers benefits only when linked to productive use, services, and jobs. Urban transport choices affect household costs and long-term emissions. When sectors are planned in isolation, costs rise and benefits fall.

Evidence from integrated land use, energy, and transport planning shows that coordination lowers costs, improves equity, and strengthens resilience. Aligning electrification with agrifood processing zones reduces post-harvest losses. Sequencing transport electrification with infrastructure and finance avoids locking in inequality. In Ethiopia, water-resilient economic and development planning together can improve both livelihoods and environmental outcomes.

Just as importantly, the research shows that public support for climate action grows when solutions improve daily life. People respond to policies that reduce food loss, create jobs, lower energy costs, and improve services. Climate strategies framed only around emissions targets risk missing what matters most.

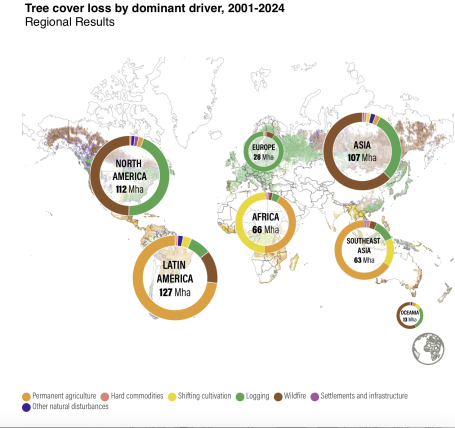

WRI Africa’s forest research reinforces this lesson. New evidence shows that forest loss in Africa is not driven by a single cause — and cannot be addressed with a single response. In parts of the Congo Basin, most forest loss is linked to shifting and small-scale agriculture, while in countries such as Ghana it is more strongly associated with commodity expansion. These differences matter: effective forest protection depends on aligning conservation efforts with livelihoods, land-use planning, and agricultural policy. These insights come from analysis using Global Forest Watch data.

The lesson is simple but powerful: climate action works best when it is integrated, locally grounded, and centered on livelihoods. When planning reflects how people live and work, and climate and development goals reinforce each other — instead of competing.

What this means

Taken together, this research points to a clear conclusion: the next frontier of climate and development progress in Africa lies not in new technologies or strategies alone, but in delivering existing solutions more effectively at sub-national level. Aligning evidence, finance, and governance where people live and work is essential to turning ambition into impact.

This calls for greater investment in subnational governments and local institutions, better use of data in planning and budgeting, and financing approaches that reflect local realities. As climate risks intensify and fiscal space tightens, progress will depend on collective efforts to move beyond plans and pilots toward solutions that work in practice — and at scale.

Read more

Ajwang, B., L. Concessao, P. Kumari, N. Ginoya, and V. Sahay. 2025. Powering agrifood systems: Review of enabling policies in Kenya, Uganda, and India. Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at doi.org/10.46830/ wriwp.22.00080.

Collins, N., B. van Zanten, I. Onah, L. Marsters, L. Jungman, R. Hunter, N. von Turkovich, J. Anderson, G. Vidad, T. Gartner, B. Jongman. 2025. Growing Resilience: Unlocking the Potential of Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Resilience in Sub-Saharan Africa. © World Bank.

Ireri, B., A. Nemera, A. Ngowa, B. Mutua, and N. Nthambi. 2025. Unlocking public finance for clean energy investment through integrated planning and budgeting in Makueni County, Kenya. Working Paper. Addis Ababa: WRI Africa. Available online at doi.org/10.46830/wriwp.23.00113.

Ireri, B., L. Concessao, and S. Sinclair-Lecaros. 2025. An approach to powering unelectrified and under-electrified healthcare facilities. Expert Note. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at doi.org/10.46830/ wrien.24.00046.

King, R., N. Shah Naidoo. 2025. Multilevel action for community-led climate resilience in informal settlements. Expert Note. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. doi.org/10.46830/ wrien.25.00083

Mbeche, R., Ateka, J., Obebo, F., Wangu, J., Chomba, S. 2025. Food Loss and Waste in Maize, Potato, Fresh Fruits, and Fish Value Chains in Kenya. Report. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute.

Mwangi, A., I. Abubaker, J. Kipkirui, and A. Oursler. 2025. Assessing supply chain barriers to and opportunities for advancing road transport electrification in Kenya. Working Paper. Addis Ababa: WRI Africa. Available online at doi.org/10.46830/wriwp.23.00088.

Ngowa, A., X. Chen, and B. Ireri. 2024. Unlocking local private capital to finance the productive use of renewable energy (PURE) sector: A look at East African local financial institutions (LFIs). Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at doi.org/10.46830/ wriwp.23.00102

Ronoh, D., D. Mentis PhD, S. Odera, T. Sego, and C. Tanui. 2025. Application of GIS in sub-national energy planning in Kenya: Integrating primary data into a least-cost electrification model using OnSSET (case study of Narok County, Kenya). Practice Note. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.46830/wripn.23.00040.

Sanniti, S., J. Kazungu, C.Reddin, E. Ruzigamanzi, B. Lipinski, and J. Wangu. 2024. The role of faith-based organizations in tackling food loss and waste in Rwanda: A preliminary study. Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at doi. org/10.46830/wriwp.22.00135.

Seyoum, Y., and H. Abebaw. 2024. Assessment of the monitoring and evaluation system’s effectiveness in a forest and landscape restoration project under Ethiopia’s REDD+ Investment Program. Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at doi.org/10.46830/ wriwp.23.00159.

Shah Naidoo, N., S. Sanniti, C. Malhotra, M. Doust, and P. Batra. 2024. Stronger NDCs with cities, states, and regions: Recommendations for national governments. Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at doi.org/10.46830/wriwp.24.00038.

Swedenborg, E.L., Z. Adane, T. Yohannes, and F. Battistelli. 2025. Water-resilient economic development planning in Ethiopia. Working Paper. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at doi.org/10.46830/wriwp.22.00107.

Ronoh, D., D. Mentis PhD, S. Odera, T. Sego, and C. Tanui. 2025. Application of GIS in sub-national energy planning in Kenya: Integrating primary data into a least-cost electrification model using OnSSET (case study of Narok County, Kenya). Practice Note. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute. Available online at: https://doi.org/10.46830/wripn.23.00040.